Mendelevium Mon Amour

What I Learned from Memorizing the Periodic Table

By Taney Roniger

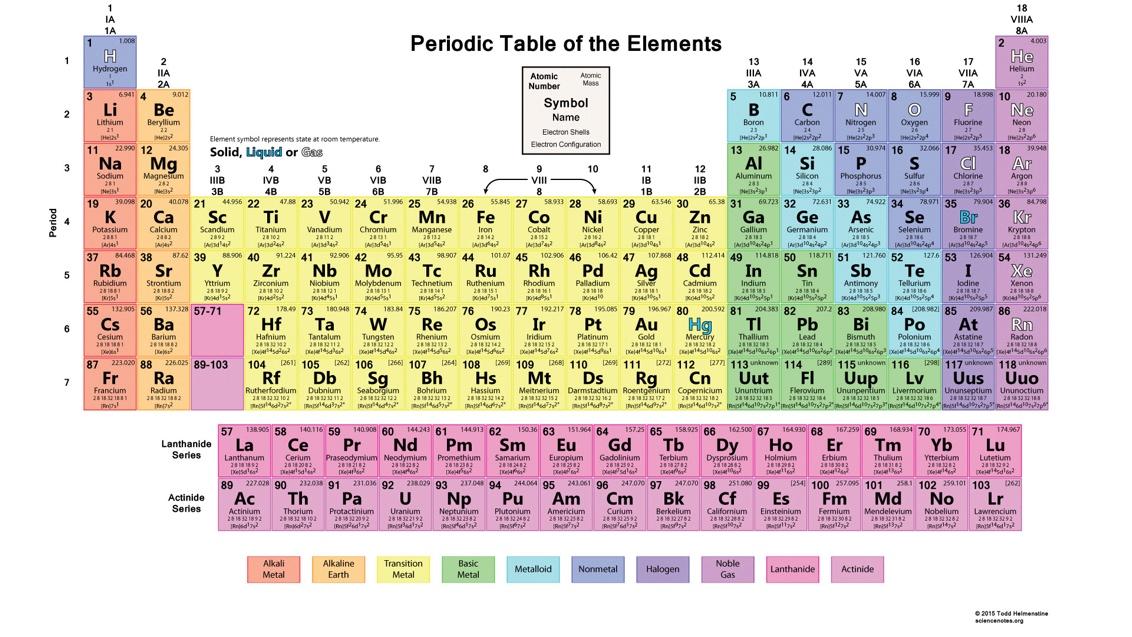

On the first day of my tenth grade chemistry class, we all watched transfixed as my teacher, Ms. Anscombe, unfurled a large banner bearing an image of the periodic table and, in a moment of high theatre uncharacteristic of high school science, proudly installed it over her desk. I was instantly smitten. Replete with colors and symbols and arcane little numbers, the table had an artistry about it, an authoritative elegance. And who could argue with the impeccable order of the thing: the way each element, represented by its chemical symbol, occupied its own little box, all the boxes lined up in neat columns and rows. As Ms. Anscombe began to explain the different properties of the elements – how each had a different number of protons in its nucleus, how some wanted to hook up with other elements while others, such as the noble gasses, were perfectly happy to be alone – I imagined them as gods, a pantheon of little mischief-makers smiling down at us from their celestial version of Hollywood Squares.

I was never, let us be clear, going to be a chemist. I knew early on that art was to be my thing. But while I quickly lost interest in beakers and Bunsen burners, the table never released its grip on my psyche. As Ms. Anscombe waxed ecstatic about isotopes and ions, I'd gaze up lovingly at the mighty array. I was sad when the year ended and I would be moving on to physics.

So it was with a whiff of nostalgia that I received from my husband for Christmas last year a small Lucite paperweight bearing an image of the table. "It's exquisite!" I beamed. Looking back, my enthusiasm must have disappointed him a bit, so much did it eclipse what I'd given the $300 camera that had come before. We spent the better part of Christmas day discussing my paperweight.

And sure enough, it wasn't long before an idea took hold. Over the course of the next few months, I decided, I would memorize all the elements in order of atomic number and recite them as a poem for my nieces and nephews. This was quickly amended. "No, no – not just a poem," I effused to my husband. "I'm going to perform them as a cheer, pom-poms and all!" I envisioned the video: Arms up, arms to the side, a swift kick in the air, all to the beat of "Hydrogen, helium…" At the end I'd raise the pom-poms, twinkle them about, and shout, cheerleader-style, "Goooooooo elements!" As someone who, while emphatically never a cheerleader, had something of a proud history as an amateur mnemonist, I knew this was a challenge I could embrace with verve.

But unlike the other facts and figures I'd committed to memory over the years (the distance of the earth from the sun? Easy: 91.483 million miles; all the countries in Africa in alphabetical order? Ask me anytime), the elements were going to be a special challenge. For as anyone who's checked recently might agree, some of the names seem borrowed from some extraterrestrial language. Meitnerium, ytterbium, dysprosium, praseodymium: not exactly the kind of words that roll off the (human) tongue. But forge ahead I would, for I was determined.

I decided it would be best to proceed in quartets – to memorize, that is, four elements at a time. If I took on one new quartet each week, I would have plenty of time to let the words sink in, and the relaxed pace would keep things light and spirited. The rule was that each time I practiced a new quartet I had to start at the very beginning, all the way back with hydrogen. Repetition, after all, is the soul of mnemonics.

In the beginning my plan proved easy enough, for unlike the alien words cited above, the first few rows of elements were mercifully familiar. What's more, when recited in fours they formed a nice rhythm. Hydrogen, helium, lithium, beryllium / boron, carbon, nitrogen, oxygen / fluorine, neon, sodium, magnesium: what wasn't to like? Occasionally the order of the quartets would trip me up, but once I came up with reasons why, say, oxygen should lead necessarily into fluorine the progression came to seem natural enough (answer: because both involve the mouth, for breathing in the first case and brushing the teeth in the second (think fluoride toothpaste), with breathing occurring before brushing, developmentally speaking). All was going swimmingly. It was fun to practice while driving or in the shower. I fantasized about which cheerleading moves would accompany which elements.

It was with scandium (quartet six, element 21) that things started to change. First of all, who on earth had heard of scandium? What was it, some kind of metal? And then…well, it just wasn't a word fit for poetry; it did not have, as they say in food culture, a good mouth feel. And worse lay in wait right around the corner. Vanadium, manganese – did these not sound like diseases? Then, after a welcome string of friendlies (iron! cobalt! nickel! copper!), germanium and arsenic, and a few boxes later rubidium and strontium. Strontium. Jesus. A quick glance at the coming rows told me things were only going to get worse. How could I not have noticed in tenth grade that some of the gods were mangy beasts? The aural flow of my recitation was really beginning to suffer. This was, after all, to be delivered as a cheer, and I could barely even read the table without stumbling over myself.

As if all that weren't enough, the memorization itself started to demand new techniques. While words that are familiar are conceptualized effortlessly (read the word "copper," for example, and you see it right away), unfamiliar words leave your brain in the dark. Lacking a ready image or concept, the brain reaches for the nearest thing it can grab – typically a known word similar to the unknown one in sound or appearance. I realized I was going to have to create a narrative made up of characters thus associated with the alien words – to convert, that is, the beasts into lap dogs. So it was, for example, that xenon became Xena the Warrior Princess, cesium became Julius Caesar, and barium became Barry Manilow, the latter of whom, brandishing a lance, led right into lanthanum, etc. With this new approach there were times when the elements had to do unseemly things, such as when Vanna White had to strike a poet with a crowbar outside a medical clinic in Scandinavia (I'll spare you the details, but the scene involved vanadium, scandium, titanium, chromium and manganese). Some scenes had to be downright obscene.

I struggled on. My pace started to lag. Weeks would go by in which I'd do nothing but recite the elements I'd already memorized. I began to question the venture as a whole. By this time I'd covered 56 elements, and dammit, wasn't that good enough? Would my nieces and nephews notice if I left off the last 62? (Actually, smarty pants that they are, they probably would.) But who was I fooling; I knew I had to finish the job, for I'd long since realized I was doing this for myself. I had to figure out a way to see it through.

Then, just when I was starting to despair, something happened. During the week of quartet 15, I asked my husband to look into buying some magnets that I needed to hang some drawings in a coming show. Expert that he is in all things engineering, he quickly found just the right product, and a week later my box of magnets arrived. Eager to try them out, I ripped open the package, and there it was in little bold letters: NEODYMIUM. My new magnets were made of neodymium. My neodymium – element 60 of quartet 15 – the very one I'd just committed to memory!

At the risk of overstating things, I'll confess that at the time this felt like a Helen Keller/Annie Sullivan moment. For suddenly I knew not only what I needed to do but indeed what I longed to do with startling urgency: I needed to learn about my elements. I set down the magnets, rushed to the computer, and googled my new friend neodymium. And there it all was: the person who discovered it, where it's found in the earth's crust, in what countries it's mined, with what other elements it acts and reacts, what it's used and best known for, and – not least – beautiful images of its silvery substance. Then came strontium, then scandium, then bromine and rubidium – one by one I went through them learning all I could about each. And one by one, what had before been mere words – and words made to act in bawdy narratives, at that – became real things in the real world with qualities and propensities.

My enthusiasm restored, I dove back into the quartets with redoubled determination. Also, for the first time I began to wonder about the origin of the table. It was not, after all, discovered in a stream; it had to be conceived and constructed by someone – by a human being. It turns out the man's name was Dmitri Mendeleev (pronounced Mendel-LAY-ev), and the story rivals any account of artistic creation. In short: It was an epic struggle, replete with false starts, missing links, and a steady stream of detractors. What we have to remember is that before Mendeleev, there was only a heap of separate elements devoid of any connecting principle. Intuiting that there had to be some hidden order underlying them, Mendeleev finally cracked the code, and hence their arrangement into periods and groups (rows and columns, respectively). As is only fitting, the man is immortalized in the pantheon itself: sitting between fermium and nobelium, mendelevium presides over box number 101.

Things took another turn when I hit number 90 (thorium, FYI). Most immediately, for the first time I could see the end on the horizon: only 28 elements to go and I'd be waving those pompoms. Then, as fortune would have it, at just this time I received a package from my friend Alice. It was a copy of the Oliver Sacks book Uncle Tungsten, Sacks's account of his boyhood love affair with chemistry. Having heard about my latest mnemonic venture, Alice thought I might like to have her copy of the book. Actually, she insisted that I have her copy of the book. For, as her note explained, she had tried her best to read it, but too much science made her brain weep (judging from her marginalia, she'd only made it to page 40). The note ended with a postscript: "Please, whatever you do, do not send it back."

I devoured the book. For here in Oliver Sacks was someone whose love for the elements I could relate to. Sacks's love, of course, was different from my own, his coming at it from the perspective of a scientist, but his child-like enthusiasm filled me with glee. Peppered with descriptions of his thrilling (if sometimes fiery) lab experiments (as a child he'd had his own chemistry lab in his family's basement), the book gave me my first window into my elements in action. Each time he mentioned one of the elements I'd memorized, I'd squeal with delight. "Hello, sulphur! Ha – hi there, phosphorus! Ooooh it's, polonium!" And I learned countless fun facts. Which is the heaviest metal on the table? Why, it's osmium (number 76), which likes to hook up with its neighbor iridium to form the alloy called – wait for it – osmiridium! (Should there not be a rock band called Osmiridium?) Alongside Alice's marginalia – little scribblings saying things like huh?? and way over my head – I jotted my own: Wow!! OMG – so cool! Go scandium!

Preparing to send the book back to Alice, I printed out a large image of the table and, drawing circles around the quartets, added a few tips on how she might go about memorizing them. "Weep no more," my note read. "This'll just take a jiff."

Finally the day came: Nearly eight months after my venture began, I reached the end with the appropriately named oganesson (O as in omega, the mnemonic went). The final stretch had not been for the faint of heart, for here the names crescendoed into sheer madness: meitnerium, darmstadtium, roentgenium, copernicium; nihonium, flerovium, moscovium, livermorium… But by this time I'd realized that learning something about the elements – especially, in this case, after whom or what they were named – helped render them tame. In fact, I was so eager to finish that I ripped through the last three quartets in a single week. Ecstatic over the victory, I couldn't stop reciting them all the way through. During a long drive to Maryland, I regaled my husband with nonstop recitations. "Forwards or backwards?" I'd ask (note to prospective memorizers: if you can do it forwards you can just as easily do it backwards; you will, after all, know exactly who sits next to whom). "Backwards," he'd say, and I'd begin again. When his eyes would begin to glaze over I'd stop for a while, only to pick it back up after, say, lunch.

I soon learned, however, that not everyone was going to be as enthusiastic as he. Not long after my day of victory I found myself mentioning my feat to a guy sitting next to me at a dinner party. "Why?" was his response. "Why memorize anything these days when we have all the information we could ever want right at our fingertips? Why not free up your brain for more important things?" "Because…" I stammered. "Because, well…" After a few false starts I finally offered this: "Because, like, next time I'm at a dinner party and some blowhard starts going on about how bronze is his favorite element, I can raise my hand and say, 'Excuse me, where exactly is bronze on the periodic table? Is it between europium and gadolinium? Or maybe between protactinium and uranium? How about between molybdenum and technetium? Because, by gosh, I've not seen it there myself.'" Looking at this guy's face it occurred to me that he might be that blowhard.

Blowhard or not, the guy had clearly rattled me. Surely he had a point, no? Was I just wasting perfectly good brain cells on useless information? Could these same brain cells not be better spent elsewhere? I stewed over it for a day or so but then had an epiphany. No, I was not wasting brain cells on useless information. For wasn't this exactly the point? During my eight months with the table, the elements had ceased to be mere information to me and had become things I genuinely cared about. You cannot spend so much time attending to something without first becoming curious about it, and then, indeed, coming to care about it, at least a little. What's more, isn't attention – the act of attending — exactly what is in such short supply today? Are we not suffering from a culture-wide failure to attend – to attend deeply no matter how foreign what we're attending to may seem to us? We go to the internet for information, but the knowledge we gain this way is acquisitional, impersonal – and, probably for this reason, very often fleeting. We do not attend in order to know. I may know a bit more about the elements than I did before, but knowledge for its own sake was never the goal. For attention is neither mastery nor acquisition; if we're to believe Simone Weil, it is, in fact, the highest form of love. Forget memorization. I'm going to call what I did an act of mnemonic devotion: a way of establishing an intimacy with something I respect – of making it a part of myself, not as a possession, not as knowledge, but as something more like a beloved friend.

But I can see you're left with a vexing question. Okay, fair enough: Does memorizing something always lead to your caring about it? This I do not know. If I memorized the names of all the quarterbacks in the NFL, I'm not sure I'd care any more about football than I do now (which is precisely not at all). Same goes for the components of a car engine, and a million other things besides. But perhaps I'm underestimating myself. If in Part II of this essay I wax ecstatic about appliance manuals or, god forbid, fly fishing, we'll know I really am onto something. But in the meantime, one important task remains for me: I need to master some cheerleading moves to accompany my recitation. The task is not to be taken lightly, and indeed it may prove the hardest challenge yet. It's not the ridicule of my nieces and nephews that gives me pause, though I do not relish the thought of this. It's that after all we've been through together, the last thing I want to do is disappoint my old friends.

____

Addendum: And here they are, in order of atomic number:

Hydrogen, helium, lithium, beryllium / boron, carbon, nitrogen, oxygen / fluorine, neon, sodium, magnesium / aluminum, silicon, phosphorus, sulfur / chlorine, argon, potassium, calcium / scandium, titanium, vanadium, chromium / manganese, iron, cobalt, nickel, / copper, zinc, gallium, germanium / arsenic, selenium, bromine, krypton / rubidium, strontium, yttrium, zirconium / niobium, molybdenum, technetium, ruthenium / rhodium, palladium, silver, cadmium / indium, tin, antimony, tellurium / iodine, xenon, cesium, barium / lanthanum, cerium, praseodymium, neodymium / promethium, samarium, europium, gadolinium / terbium, dysprosium, holmium, erbium / thulium, ytterbium, lutetium, hafnium / tantalum, tungsten, rhenium, osmium / iridium, platinum, gold, mercury / thallium, lead, bismuth, polonium / astatine, radon, francium, radium / actinium, thorium, protactinium, uranium / neptunium, plutonium, americium, curium / berkelium, californium, einsteinium, fermium / mendelevium, nobelium, lawrencium, rutherfordium / dubnium, seaborgium, bohrium, hassium / meitnerium, darmstadtium, roentgenium, copernicium / nihonium, flerovium, moscovium, livermorium / tennessine, oganesson.